In 2012, I was wandering around Netflix’s (back then meagre) selection and picked a 2010 rom-com starring Anne Hathaway and Jake Gyllenhaal. In it, Jamie is a successful drug rep, navigating around hospitals and conventions, pressing Viagra into rich men’s hands. He meets Maggie, a beautiful young woman with stage 1 Parkinson’s disease. Of course, they fall in love, because otherwise it wouldn’t be a rom-com.

So I watched it, and fell in love with it. Bought the DVD, and watched it twice more in the following year, loving it even more every time.

Back in 2012, my diagnosis was just over a year old; I still walked relatively normally, and mobility aids were something I didn’t even think about. I didn’t yet consider myself disabled, and wouldn’t do so for a number of years still. Over the next few years, Netflix started producing its own stuff, my to-watch list became unmanageable, and I didn’t have the time to rewatch this movie I had loved so at a time. Until last month, when I decided to give it a go in order to write a post about it here. I was fully prepared to be disappointed, as I was now watching it as a fully disabled woman who has been disappointed by Hollywood’s portrayal of disability before.

Reader, I was not disappointed. The thing holds up!

The movie never shies away from Maggie’s disability, never tries to hide it or make us forget about it. In fact, in the first scene where we meet her, she’s in a doctor’s office rambling off a long list of the medications she’s on and of specialists she’s seen—something that will be annoyingly familiar to many of us. We regularly see her take her medication, have difficulty opening a bottle (or a Pop-Tart wrapper, as in the screencap above), have some of the little shakes of her disease, meets other people with Parkinson’s…

And yet, through all this, her condition never takes centre stage. The film stays a rom-com, and Maggie stays a person. There is a lot of sex, which probably comes as a surprise to ableds who think disabled people never have sex (especially not with “normal” people!), and able-bodied Jamie is the one who runs after disabled Maggie, not the other way around. She is at first reluctant to let anybody in, to let anybody love her and her broken body, which is a sentiment I can totally understand, and he’s the one trying to convince her to let him love her. He’s even the first one to say “I love you,” which leads Maggie to tell him it doesn’t mean anything, and that she “once said it to a cat.”

At the end of the movie, after what Maggie thought was the final break-up and that she’s never going to see Jamie again, he tracks her down and tells her again that he loves her, that she needs him but he needs her too. “I’ll need you more than you need me,” she tearfully replies. He’s okay with this. And it reminds little disabled single me that such people exist.

(And then they live happily ever after.)

That is something else I can absolutely relate with; not wanting to be a burden to anyone, avoiding relationships so as not to feel like one. Disabled people are not burdens, of course, and plenty of them are in healthy relationships with significant others, but that’s what internalized ableism does to you: it makes you afraid that your mere existence will inconvenience others.

My favourite bit of the movie is when they go to a convention in Chicago, and she wanders across the street where there is a discussion group of people with Parkinson’s disease. And I was glad to find out later that this was a real group, and that those who spoke were real people with the disease. In fact, I would bet anything that they wrote their own lines, because the fantastic “who knew God wanted us to be so good at giving hand jobs?” line can only have been written with the self-deprecating humour of somebody living with that disability, and not by an abled who thinks we’re all dainty porcelain dolls.

Maggie’s reaction to that conference reminded me of what I felt when I discovered the disability community on Twitter: the realization that she is not alone, that other people live what she lives and feel what she feels. That it’s okay to see humour in your condition, that you can laugh at it while both hating it and loving yourself. Some have it better than her and some have it worse, but she has found people who understand her. Of course, she’s luckier than me in that she has a disease people actually recognize. I tell people I have something called spastic ataxia, they bless me because they think I sneezed.

While she’s living through this awesome awakening, Jamie is having his own in another room, with the partner of a woman with stage 4 Parkinson’s. His advice to this young man asking for the best way to be with his stage 1 girlfriend? “Run while you still can.” So they both come out of that weekend very different than when they came in: she is ready to go all in with the relationship, whereas he had a glimpse of what his future would be like and did not like it.

The obvious movie trope here would be for him to dump her, but instead he decides to cure her—again a reaction abled people will recognize, ableds thinking our lives absolutely need to be fixed to be worth living. He drags her around the country, to see doctor after doctor, specialist after specialist, looking for that elusive miracle cure, until she finally puts her foot down, tells him that her disease is a part of her, she’s finally okay with that and if he can’t be too, then they can’t be together.

(And then he realizes life sucks without her, he begs her to take him back, she does, and they live happily ever after.)

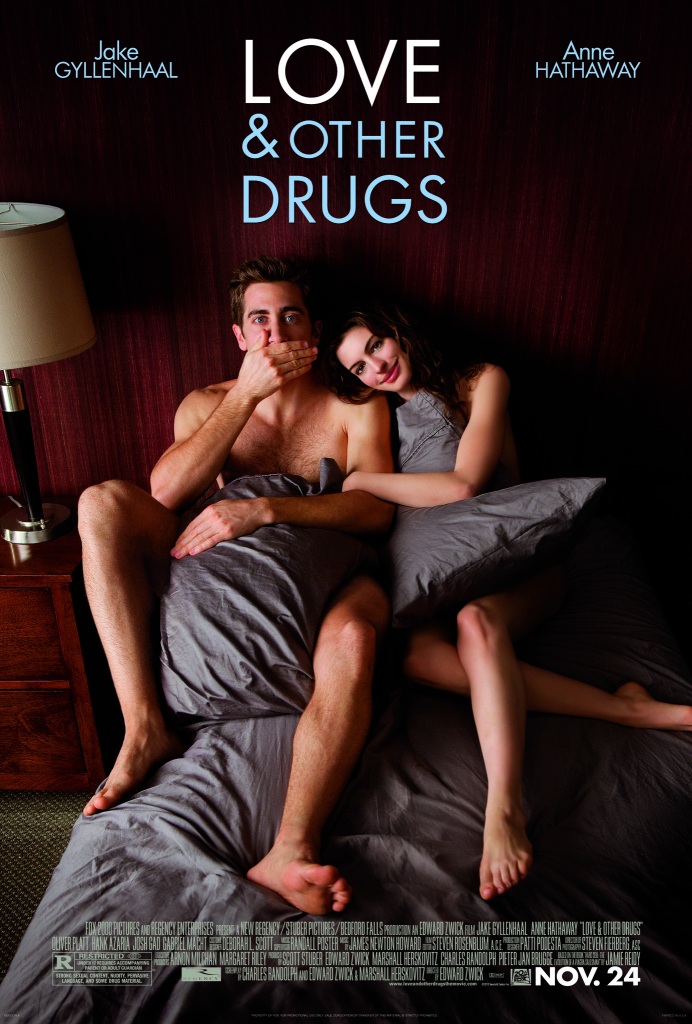

Of course, this is Hollywood, and we know that in Hollywood, disability doesn’t sell. The poster does not contain a single hint about Parkinson’s, but I guess that’s okay, since it’s not like she uses a mobility aid or anything (though would it have killed them to add a bunch of pill bottles on her bedside table? I mean, “drugs” is right there in the title!)

Putting aside the poster for a minute, let’s take a look at the blurb printed on the DVD case:

Maggie (Hathaway) is an alluring free spirit who won’t let anyone—or anything—tie her down. But she meets her match in Jamie (Gyllenhaal), whose relentless and nearly infallible charm serve him well with the ladies and in the cutthroat world of pharmaceutical sales. Maggie and Jamie’s evolving relationship takes them both by surprise, as they find themselves under the influence of the ultimate drug: love.

Again, not a single mention of her disability, just of her “alluring free spirit.” The trailer also doesn’t just skirt around Maggie’s disease, it doesn’t even imply she has one at all. It seems to portray a run-of-the-mill romantic comedy about a good-looking guy who wants sex, a beautiful girl who likes sex, and then surprise!feelings appear out of nowhere. Knowing all this, I kind of understand why it got seemingly lukewarm reviews from people who didn’t like that it went too deep for a rom-com.

That being said, the general consensus in the disability (and particularly Parkinson’s) community is that while it may not be the best movie ever, it got disability and the feelings around it spot-on. And now you can add me to this list of disabled people who saw themselves in the film.